A New Path Towards a New Constitution: Chile’s 2023 Constitution-Making Process

/Gonzalo Candia, Tom Gerald Daly, Anna Dziedzic and Alejandra Ovalle

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile & Melbourne Law School

In October 2020, following the nationwide protests of 2019-2020, a majority of almost 80 per cent voted in favour of a process to rewrite Chile’s constitution. The new Constitution would replace the 1980 Constitution promulgated under the authoritarian Pinochet regime. The Constitutional Convention began work in July 2021 and produced a draft constitution (English translation here) after a year-long constitution-making process. However, on 4 September 2022 the Chilean public, in a nationwide referendum, rejected this draft constitution.

Much ink has been spilled on the reasons for this rejection (see here and here). In fact, there is still no agreed explanation about the reasons that led the electorate to vote as it did. Some of the reasons argued by those who have wanted to explain the outcome of the referendum include: the perception that the proposed constitutional text was too radical, the negative evaluation of the confrontational attitude that prevailed among the members of the Convention, a lack of clarity among the public concerning the process and content, and the perceived inability of Constitutional Convention members – many of whom were independents – to achieve generally acceptable agreements. There were also concerns about deficiencies in the Convention’s procedures, including time management in settling the rules, facilitating meaningful public participation, and allowing for harmonisation of the text throughout the process.

This post describes the new constitution-making process (commonly referred to as the “constituent process”) that has recently been settled by the principal political parties and offers a preliminary analysis of its key features and points of distinction from the first process. As we finalised this piece, a useful analysis has just been published here: we encourage readers to read that analysis and we have aimed to ensure that both analyses are complementary.

The New Constitution-Making Process: Chronology

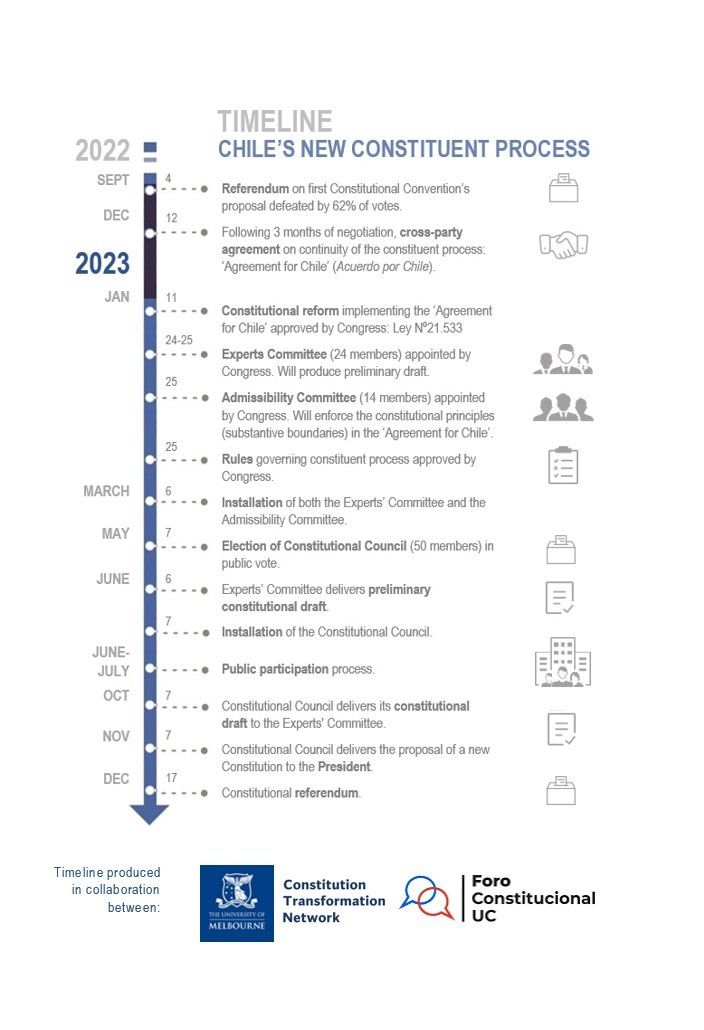

Table 1 Constitution-Making Process Timeline:

4 September 2022

The referendum to close the first constitution-making process took place. The Constitutional Convention’s proposal is defeated by 62% of votes.

12 December 2022

After three months of negotiation, most parties from across the political spectrum reached an agreement to continue the constitution-making process. This political document is called “Agreement for Chile” (Acuerdo por Chile).

11 January 2023

The constitutional reform that implements the “Agreement for Chile” is approved by Congress. It is published in the official bulletin on 17 January 2023 (Ley Nº21.533).

24-25 January 2023

Congress appoints the 24 members of the Experts’ Committee, tasked with elaborating a preliminary constitutional draft. Appointments are made in proportion to political representation in Congress and respecting the principle of parity between women and men.

25 January 2023

Congress appoints the 14 members of the Admissibility Committee tasked with enforcing the 12 constitutional principles (substantive boundaries) contained in the “Agreement for Chile”. Appointments are made in proportion to political representation in Congress and respecting the principle of parity between women and men.

25 January 2023

Congress approves the Rules for the constitution-making process, drafted by a special commission of members of both chambers of Congress.

6 March 2023

Installation of the Experts’ Committee and the Admissibility Committee. The Experts’ Committee will elaborate a preliminary constitutional draft; approval, rejection, and amendment of its provisions will require a three-fifths majority.

7 May 2023

Citizens elect the 50 members of the Constitutional Council, according to the electoral rules of the Senate and respecting the principle of parity between women and men. There will be supernumerary seats reserved for members of the Indigenous population.

6 June 2023

The Experts’ Committee will deliver the preliminary constitutional draft, which will serve as terms of reference for discussion within the Constitutional Council.

7 June 2023

Installation of the Constitutional Council, tasked with discussing and approving a final proposal for a new Constitution, based on the preliminary draft of the Experts’ Committee. Proposals and amendments will require a three-fifths majority, both in committees and plenary. The final proposal must be completed within five months.

June-July 2023

Public Participation

Submissions of citizens’ proposals to the Constitutional Council (7 June-7 July)

Public hearings (7-14 June)

Citizens’ dialogues (7 June-7 July)

On-line consultation (7 June-7 July)

7 October 2023

The Constitutional Council will deliver its first constitutional proposal to the Experts’ Committee, which will harmonise the text and set out its observations. If there is a disagreement between the Constitutional Council and the Experts’ Committee, a special commission comprising 6 members of the Constitutional Council and 6 members of the Experts’ Committee to negotiate agreement.

7 November 2023

The Constitutional Council will deliver the final proposal of new Constitution to the President.

17 December 2023

Constitutional referendum.

The shareable infographic below summarises this new process.

Issues for consideration

Legal status: An interesting feature of the process, from a comparative perspective, is that political agreements regarding the first constituent process and the continuity of the constitution-making process have been enshrined in successive constitutional amendments to the current Constitution, approved by Congress. This option aims to strengthen the idea of a constitution-making process in the context of a functioning democracy, in addition to clearly limiting the function of the constituent body to the task of proposing a new constitutional text. This approach is fully consistent with a tradition of legality that is part of the history of Chilean constitutionalism.

Drafting bodies: The new constitution-making process features two key drafting bodies: the Expert Committee (24 members) and Constitutional Council (50 members). The members of the first body were appointed by Congress on 24-25 January 2023, while the members of the Constitutional Council will be selected at elections scheduled for 7 May 2023. The Experts´ Committee is responsible for elaborating a preliminary constitutional draft, which will be the basis for the Constitutional Council’s deliberations with the aim of approving a final proposal of a new Constitution. Experts will participate during the Constitutional Council's deliberations (without the right to vote) and both bodies will have some joint powers during the final drafting phase. Together, counting 74 individuals in total, these bodies are significantly smaller than the 155-member Constitutional Convention elected for the first constitution-making process.

Supervisory Body: A third body, the Admissibility Committee (14 members), will play a key role in ensuring conformity between the 12 principles (known as ‘bases institucionales’) in the “Agreement for Chile” and the new constitutional text. This Committee will function as a kind of referee, resolving controversies concerning the application of those principles during the drafting process. Due to the open-textured character of the principles, it will be crucial to the process how this Committee understands the scope of its own powers in practice.

Inclusion and Exclusion: Four features are relevant here. First, membership of the Experts’ Committee, Admissibility Committee and Constitutional Council will respect the principle of parity between women and men; a notable feature of the first constitution-making process. Second, there will be reserved supernumerary seats for members of Indigenous communities, with seats assigned according to the percentage of effective voting at the election. This is likely to result in fewer Indigenous representatives in the main deliberative body than in the first constitution-making process. Third, the election of the Constitutional Council does not consider special rules to favour the elections of independent candidates (unlike the previous process). Fourth, members of the Constitutional Convention established for the first constitution-making process of 2021-2022 are ineligible to stand for election to the Constitutional Council in the new process. As a result, it seems likely that the new process will involve more experts and representatives affiliated to the main political parties, in contrast to the diversity of the first Constitutional Convention.

Timeline: The new constitution-making process allocates under eleven months in total, and just 8 months between the installation of the drafting bodies and presentation of the draft constitutional text to the President. This can be compared to the first process, which took 12 months (albeit with 3 months dedicated to the elaboration of the Rules). Although this period is not unusually short, and the first Constitutional Convention managed to complete its task within the time allotted, the issue of managing timelines effectively will be crucial for the new process. The Experts’ Committee, in particular, must complete its preliminary draft within three months.

Approval Procedures: The Experts’ Committee and Constitutional Council will make decisions by a three-fifths majority, a slightly lower voting threshold than the two-thirds majority decision-making in the first process. Importantly, the referendum on the proposed constitutional text will entail compulsory voting and approval by a simple majority to pass.

Concluding Thoughts

The new constitution-making process can fairly be viewed, to some extent, as a reaction to perceived deficiencies in the first process, including a view that the drafting process was too open-ended, or at least that insufficient attention was paid to coherence, harmonisation and oversight. Open questions include what use the drafting bodies will make of the text produced by the first Constitutional Convention, how robustly the Admissibility Committee will approach its task of enforcing the “Agreement for Chile”, and to what extent public participation will influence the text. As it stands, the second process is a testament to the continued determination to replace the Pinochet-era text with a new constitutional document capable of reflecting more fully the democratic realities and aspirations of communities across Chile. It is a process that will be closely watched by those interested in constitution-making worldwide.

Postscript: A Valuable Collaboration

This blog post is part of a collaboration between the Constitution Transformation Network (CTN) at the University of Melbourne and the Foro Constitucional at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. After initial discussions in June 2021 between Cheryl Saunders and Francisco Urbina, the collaboration has blossomed into a full working group including Alejandra Ovalle, Gonzalo Candia (and since 2023, Sebastián Soto) on the UC side and Tom Daly and Anna Dziedzic on the CTN side.

Our first report on managing deadlines was published in September 2021 in Spanish and English, just as the Constitutional Convention commenced its work. Our work focussed on the issue of time management in constitutional processes, setting out the key phases and issues that might arise as constitution-making deadlines approach. This collaboration brought together the UC team’s granular knowledge of the Chilean process and the CTN team’s broad comparative knowledge, drawing lessons from constitution-making processes in Nepal, South Africa and Brazil. During 2023 we will continue to work together to better understand Chile’s new constitution-making process and to divine key lessons for a global audience.

Gonzalo Candia is Assistant Professor at the Department of Public Law and Member of the Foro Constitucional at Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

Tom Gerald Daly is Deputy Director and Associate Professor of the School of Government at the University of Melbourne and Convenor of the Constitution Transformation Network at Melbourne Law School.

Anna Dziedzic is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Laureate Program on Comparative Constitutional Law and Convenor of the Constitution Transformation Network at Melbourne Law School.

Alejandra Ovalle is Associate Professor at the Department of Public Law and Director of the Foro Constitucional at Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

Suggested Citation: Gonzalo Candia, Tom Gerald Daly, Anna Dziedzic and Alejandra Ovalle, ‘A New Path Towards a New Constitution: Chile’s 2023 Constitution-making Process’ IACL-AIDC Blog (9 February 2023) https://blog-iacl-aidc.org/2023-posts/2023/2/9/a-new-path-towards-a-new-constitution-chiles-2023-constitution-making-process.

![Xx1088_-_Seoul_city_nightscape_during_1988_Paralympics_-_3b_-_Scan [test].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5af3f84a4eddec846552ea29/1527486925632-3VZP3ASLAHP1LJI0D9NJ/Xx1088_-_Seoul_city_nightscape_during_1988_Paralympics_-_3b_-_Scan+%5Btest%5D.jpg)